The Billy Hart One is the Other band make it high up the list photo: ECM

A small glimpse of where we are in jazz this year courtesy of three piano trios, three drummer-led bands, a prog-jazz duo, five albums fronted by trumpeters, a certain piano-bass duo playing standards, a singer, two piano-less sax trios, an extraordinary violin-piano duo, no-holds-barred free improv, some new octet “spectral” sounds, and an old fashioned tenor sax hero

20 Neil Cowley Trio Touch and Flee Naim Jazz

Curious album cover: mannequin fingers on beardy hair, Britain’s best known contemporary jazz piano trio return with a pared down introspective album very different from the with-strings bravura of The Face of Mount Molehill. A band that has popularised the collision between chill-out and dance music-inspirations and a post-EST sense of improvising with its own particular language, the Neil Cowley Trio know what it means to explore the possibilities of the piano trio when there is no obligation at all to swing. Their last album, the fine live CD/DVD Live at Montreux quietly released last year, was a summation to a certain extent: the story so far gathering together large chunks of Cowley material since the band’s inception. Now nearly a year on since its release with nine all-new songs, no strings this time, although Dom Monks who produced The Face of Mount Molehill is again a vital part of the monumental sound of the record once again handsome, it’s a more reflective Cowley to an extent in the early part of the album. Sure it’s still very melodic and accessible but there is less blood and guts, even Evan Jenkins is that bit more restrained, and the improvising reaches land it has never found before. The writing as usual isn’t easily pinned down, Cowley avoids jazz cliché and he improvises by building his tunes section by section, so it’s highly detailed structured writing grounded on strong themes, the best of which is the reverb-soaked opener ‘Kneel Down’. Cowley taps out a more chromatic crab-like direction on ‘Couch Slouch’ extending himself a little and allowing the trio more room. Sometimes there’s just too much piano, the bass and drums overshadowed by the sheer garrulousness of Cowley. But ‘Bryce’, like the opening tracks is more nuanced, and you can feel Cowley is trying to create a new space for the trio. It is a different sound. The electronics at the beginning of ‘Mission’, the track that got a bit of pre-release radio play over the weekend, are a surprise, like an arcade game synthy commentary before the most powerful theme of the whole album emerges coated in glorious sonic detail. So a very different trio, more naked than Molehill for sure. Cowley’s writing has changed considerably and it’s less cheeky chappie and more the serious artist that comes across. The album needs a bit of living with given the changes: ‘The Art’ at the end yet another heavy statement of brand new intent.

19 Jeff Ballard trio Time’s Tales OKeh

Time’s Tales finds master drummer Ballard leading a supergroup in all but name, as he’s joined by the innovative Herbie Hancock guitarist Lionel Loueke, and the highly rhythmic Puerto Rico-born star alto saxophonist Miguel Zenón who has personality to burn here on complex joyous runs best glimpsed on Ballard’s tune ‘Beat Street’ or on the adaptation of Béla Bartók’s ‘44 Duos for Two Violins’ on ‘Dal, a Rhythm Song’ where Zenón is poignant and tender.

An adventure with plenty of heat Time’s Tales is sure proof that metrical wizardry and subdivisions made in drummer heaven need not interfere with the vitality of the music as music. Indeed the sheer quality of the interplay means the technical feats melt away and you can actually reach the emotion of the playing which is partly the point after all so that the music speaks to you. The album opens with a great reminder of Obliqsound-period Loueke with ‘Virgin Forest’ the title track of an early album of the Benin-born guitarist's where his legend as a leader first began to surface. And there are other surprises: perhaps you wouldn’t expect the inclusion of ‘The Man I Love’ yet it fits in well as the album approaches its mid-point with Zenón all heart-on-sleeve on the classic Gershwin ballad. The energy of grown-up teenagers at heart letting off a bit of steam surfaces in the trio’s take on the Queens of the Stone Age’s ‘Hangin’ Tree’, a bit of fun, but much more rewarding is the experimental ‘Free 3’ at the end (hinted at earlier on the brief ‘Free 1’), which has real edge and above all openness. An album with more than its fair share of tenderness, Zenón is on fire pulling off some of the most direct playing of his career, and Loueke utilises the soukous and Franco-influenced side of his sound to magical effect painting vivid expressionistic brushstrokes all over this fine record Ballard has also produced. Go to sleep tonight and dream that your local club has the artistic sense as well as the wherewithal to book this gifted trio.

Come here often? Photo: Nonesuch

18 Mehliana Taming the Dragon Nonesuch

Enter the duo of Brad Mehldau and Mark Guiliana, and there’s a story to tell to begin with, the spoken word voice of Mehldau channelling his inner Kerouac on the monologue of title track opener ‘Taming the Dragon.’ Spoken against eerie keyboards washing in and out here’s a taste of what the narrator has to say: “I had this trippy dream where this cat was driving me around in an old convertible the whole time around LA. Later on it turned into a VW van and near the end it was more like this spaceship kind of thing. We were high up looking over the road.” It turns out that the narrator is being driven round by an old hipster with a scratchy voice, a cross between Joe Walsh and Dennis Hopper apparently, and then driving north on the Pacific Coast Highway there’s an incident with a sports car coming out of nowhere that cuts the pair of them up. The dude the narrator is with stays calm but the narrator himself in the passenger seat is fuming, “puffed up and pissed off”, but yet admires his driver’s cool. Of course it turns out it was all a dream and everybody in the dream was the narrator. The music interweaving has a kind of pumped up pogo-ing intensity as the track unfolds which is kind of exciting and put it this way a world away from the concert hall the ladies with the twin sets and the gents with the combovers like to hear the Mehldau trio in. Mehliana is about taming but not dissipating the angry side of the guy in the dream. And suitably the album has a lot going on, a roar to it, and the Fender Rhodes, synths and effects fill the ears with a pretty big sound spectrum. The synths are like the best toys you could ever want to play with and their bottom beefier end cut the air like butter to add some EDM momentum along the way with the hyper-active drums and effects part and parcel of the approach. Echo effects and a buzzy wash don’t harm anybody either in the development passages and Mehldau seems to have learnt a lot from Pat Metheny, and here on ‘Hungry Ghost’ there’s a big theme that could without being too fanciful belong on an album of Metheny's such as Secret Story. With half the album written by Mehldau and the rest co-operatively by the duo there are snatches of spoken word from other sound sources melded in and the most elaborate seems to be on the ‘Elegy for Amelia E’ track. Named for aviator Amelia Earhart whose voice is heard from a 1935 radio broadcast. Seven years earlier she had became the first woman to successfully fly across the Atlantic Ocean. Mehldau samples quite a bit of her voice after his opening spacey solo heavily processed with extra sound effects. So there’s this voice of Earhart’s sounding a bit strangulated and historic from more than 70 years ago. “Obviously,” she says matter-of-factly “research regarding technological unemployment is as vital today as further refinement or production of labour saving and comfort giving devices. Among all the marvels of modern invention, that with which I am most concerned is, of course, air transportation. Flying is perhaps the most dramatic of recent scientific attainment.” Earhart goes on to conclude that aviation “exemplifies the possible relationship of women and the creations of science. Although women as yet have not taken full advantage of its use and benefits, air travel is as available to them as to men.” The floaty phantom-like voices weave in behind her own hard-to-catch voice as the music gets louder and louder and Mehldau’s soloing becomes more and more detailed and almost fugue-like in its intensity. Mehldau staggers towards prog-jazz here and there on this track with what sounds like small explosions and the lament at the end mirrors the sad loss of the aviator after a career of extraordinary achievement. It’s one of the album’s best extended sections. On ‘Just Call Me Nige’ Guiliana comes into his own, the beats getting chopped up and the pair gallop faster and faster. So plenty of things to consider. Could this be Mehldau’s own Future Shock of an album and the Nige track his own ‘Rockit’? It's impossible to say, but a tantalising thought. Taming the Dragon is certainly a fun outing with plenty of thrills and spills along the way. You want to dance with that dude, as Joe had it in the dream? There's consequences, as the man said.

17 GoGo Penguin v2.0 Gondwana

Opening v2.0 gently with the heartbeat of ‘Murmuration’, GoGo Penguin drummer Rob Turner languidly nudging the band forward, pianist Chris Illingworth enveloping the listener in a cocoon of euphony, new bassist Nick Blacka’s processed double bass eventually rising to the sense of occasion, a dystopian dissonance ultimately against the arc of a soaring crescendo. Then ‘Garden Dog Barbecue’ provides more detail, and in keeping with their earlier Gondwana album Fanfares (Blacka replacing charismatic bassist Grant Russell) the EST comparison is unavoidable but it’s fast making less sense certainly in the totality of this deeply satisfying still unreleased new album. Turner’s drum patterns are certainly very different to Magnus Öström’s, merging more with a broken beat sensibility, and the motion doesn’t just track to trip hop and back. The band’s collective musical empathy is stronger already here than on Fanfares, which nonetheless was a fine debut. There’s a certain melancholia in the band’s sound retained that is still appealing, and a certain enhanced karmic side to their interplay where you can measure the emotional impact at certain points. ‘Fort’ simplifies and clarifies the sound while protest song ‘One Percent’ has an eerie beginning that smashes hard, and ‘Home’ introduces new timbres, the drums more metallic. It’s a tuneful album, Halifax-born Illingworth a versatile and subtle kind of virtuoso who knows how to harness the energy and lost-in-the-music abandon of a 1990s dance music generation evident in the band’s interior soundtrack with Aphex Twin and Massive Attack influences peeking through. ‘The Letter’ was recorded in the dark apparently, a technique also deployed by another New Melodic band Phronesis, yet GoGo Penguin rely less on the delayed gratification of metrical exploration than the Anglo-Scandinavian trio whose latest album Life to Everything hits three weeks after v2.0. ‘To Drown in You’ has lots of surprise detonations, jabbing drums, and rhapsodic effects, with ‘Shock and Awe’ and ‘Hopopono’ drawing an album that could easily stake its claim as the most original and accessible jazz piano trio album of new music to emerge from these shores since the Neil Cowley 2006 album Displaced, to a convincing close.

16 Linley Hamilton In Transition Lyte Records

Three years on from the much more mainstream quartet album Taylor Made trumpeter Linley Hamilton has made giant strides here in terms of moving into a new interpretative space joined once more by pianist Johnny Taylor, who like drummer Dominic Mullan returns from the earlier Lyte release. Australian bassist Damian Evans, and Italian guitarist Julien Colarossi, the latter guesting on three tracks including a mellow turn on Hamilton’s own tune the yearning ‘Dusk’, complete the quartet+ line-up. Ostensibly a ballads album material featured includes a fine treatment of Rufus Wainwright’s ‘Dinner at 8’, Hamilton clearly interested in seeing “the tears in your eyes”, and he succeeds in that difficult task. The pavane-like treatment of Abdullah Ibrahim’s ‘Joan-Capetown Flower’ delivered in appropriately stately fashion is a big plus and although the tempi on the majority of the tracks are slow that factor seems to increase the impact of the album rather than detract from it, and In Transition never drags, Hamilton preferring on his solo statements to be expressive rather than move his fingers about at a great rate and spray notes everywhere, the knowing Taylor a comping Boswell to Hamilton’s Dr Johnson. Easily the Belfast trumpeter’s best album to date the development of song-based melody with all that that onerous task involves is paramount, as an improviser Hamilton preferring to paraphrase and decorate detouring only into an overtly mainstream Thad Jones-like space on the Rodgers and Hart standard ‘I Didn’t Know What Time It Was’ where Evans begins to swing the band attractively.

A dance to the music of time

15 Keith Jarrett and Charlie Haden Last Dance ECM

More from the Jasmine session recorded at Keith Jarrett’s home studio in 2007. Two of the tracks, ‘Where Can I Go Without You’ and ‘Goodbye’, are alternate takes, the alternate ‘Goodbye’, the old Benny Goodman theme by Gordon Jenkins easily stealing the whole show. These are slow songs, the pair seem to have all the time in the world, ‘’Round Midnight’, with a very deceptive introduction, that is very inviting, could have been even slower and comes across as optimistic. ‘Dance of the Infidels’ puts Haden through his paces, the tune taken at a brisk lick but ‘It Might As Well Be Spring’, like ‘Goodbye’, is in another league in terms of interpretation, the pair completely as one. Last Dance is not about pain and suffering, and there’s something additional, approaching fraternal joy, in the playing of Jarrett and Haden here in great abundance, that’s so very striking.

14 Theo Croker AfroPhysicist OKeh

This is a download-only release so far in the UK and Ireland. Not quite sure why the label has decided to do this (‘business’ reasons?) with one of the more interesting new jazz artists who has “star” written all over him to emerge this year. The polar opposite of what’s lazily called state-of-the art, in jazz trumpet terms at the moment that’s Ambrose Akinmusire who has to my mind released the best album of the year so far, Croker instead has his own name for his style: dark funk. Blessed with great tone and timing... but wait a minute: who is Theo Croker? Born in Florida in the 1980s (he turns 29 next month), the trumpeter is the grandson of Doc Cheatham name checked on the first track ‘Alapa’ so Croker is from trad-into-mainstream jazz royalty and made his debut on a little known album called The Fundamentals (a track of the same name is included here) and equally obscure In the Tradition although that found him along with Tootie Heath as well as the pianist here, Sullivan Fortner. A winner of the Marcus Belgrave national jazz trumpet competition in the States there is a little funk in a New Orleans jazz sense and triphop (on ‘Light Skinned Beauty’) here, plus some AfroJazz (Caiphus Semenya’s ‘Bo Masekela’) mingling but at heart it’s an accessible and attractive heartland mainstream jazz record of real quality and ideas. Croker’s solo on ‘Moody’s Mood For Love’ will tell you all you need to know about where the trumpeter positions himself in terms of the tradition, eg the sound comes via the Little Jazz and Dizzy line, and Croker also compares well with the Nicholas Payton sound. Guests here include Dee Dee Bridgewater who produces the record, vibist Stefon Harris superb on Stevie Wonder’s ‘Visions’ again Croker soloing beautifully, and the wavery Roy Hargrove singing on ‘Roy Allan’, the worst track here! Tenorist Stacy Dillard (in the Lester Young mould) is a refreshing presence and ex-Mulgrew Miller and Ray Brown drummer Karriem Riggins from Detroit is a scintillating rhythmic presence comin’ atcha. Worth your time and pennies.

13 Dave Douglas/Chet Doxas/Steve Swallow/Jim Doxas Riverside Greenleaf Music

This is a bit different. It feels like a lost world, music that’s been hidden away for too long. Slightly quirky, certainly jaunty, Douglas tune ‘Thrush’ opens proceedings. The trumpeter co-leads the band with Montreal-born reeds player Chet Doxas, the pair teaming with electric bass icon Steve Swallow, and Chet’s brother drummer Jim Doxas. The main thrust of Riverside is its theme around the timeless music of clarinettist/saxophonist Jimmy Giuffre (1921-2008). Swallow was a member of the Jimmy Giuffre 3, however, the quartet's style doesn’t just leave it at just that and forges ahead to navigate weavingly around neighbouring styles that fit like a glove, so there are hints of bluegrass, sacred hymns and Appalachian music thrown in. The album was recorded over two days in Toronto in the late summer of 2012 after touring. Best bits? Well I’m a sucker for Giuffre’s classic slightly unearthly ‘The Train and the River’ with its keening squawk of a tune Doxas drumming like a wannabe punk behind Douglas and Chet’s energetic runs. Doxas’ ‘Old Church, New Paint’, introduced in a two-minute burst, and then on the full tune has Chet Doxas’ buttery tone and the slow tempo churning a lazy gospelly atmosphere you could put in a can and practically scoop out at will. Douglas’ ‘Handwritten Letter’ starts where ‘Train and the River’ left off injecting frenetic pace as a twist, while ‘Big Shorty’ is more sinewy and urban. The Trummy Young/Johnny Mercer/Jimmy Mundy standard ‘Travellin’ Light’ title track of The Jimmy Giuffre 3 1958 Atlantic album issued for the first time on CD in the UK just last year has sly period charm, another highlight. Doxas’ ‘Sing on the Mountain High/Northern Miner’ at the end is a big emphatic statement that adds weight to an album that has bags of personality and buckets of warmth.

12 Somi The Lagos Music Salon OKeh

An aural portrait of the singer’s time spent living for an extended period in Lagos, a picture of life in the city utilising those sounds Somi recorded and which then act as episodic aural street scenes interspersed between the songs. In the studio with musicians on the album who include pianist Toru Dodo, guitarist Liberty Ellman, drummer Otis Brown III, trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire and the bass guitarist Michael Olatuja, guests are the great Beninoise singer Angélique Kidjo on ‘Lady Revisited’, a song Somi introduced on her 2007 album Red Soil in My Eyes, and rapper Common on ‘When Rivers Cry’, a song about the environment and ravages of pollution. The Lagos Music Salon is an album that tackles serious issues but is neither preachy nor frothy although it has a scintillating and very accessible Afrobeat-derived sound you can, at certain points, dance to. But there is also a series of important messages inside the songs. A new version of a Nina Simone song from Simone’s classic 1960s album Wild is the Wind, which in this new version touches on the horror of genocide, is a significant highlight, while Ambrose Akinmusire’s solo on another socially conscious song, this time turning to sexual exploitation, ‘Brown Round Things’, is one of the most dramatic moments on the album, and not forgetting the romantic side in high contrast captured magically on the vivacious ‘Ginger Me Slowly.’ Smart and sassy, The Lagos Music Salon is a breath of fresh air.

With its origins in a commission by Duke University and Lincoln Center, by tackling Stravinsky’s iconoclastic work it’s the most audacious choice in terms of reaching beyond genre the piano trio of Ethan Iverson, Reid Anderson and Dave King have made to date. Something that certainly makes covering Tears for Fears shrink into the band’s back catalogue, even if that at the time of Prog was a more shocking post-modern statement. Their first album since 2012’s excellent Made Possible this is a thrilling, highly anarchic album and despite some early blurb that the interpretation is as literal as possible (bearing in mind it’s a piano trio here rather than an orchestra, presumably) takes considerable liberties with the ground breaking work and is a little longer. Iverson’s airy naked piano lines jut into piles of controlled dissonances pumping out space like a high functioning smoke machine to challenge our perceptions. Just take the opening: Stravinsky scored it for a bassoon up high in the instrument's register. The Bad Plus might have caused their own kind of riot if TBP had smuggled that baby in. By the end Dave King’s tattoo of tribal abandon on the ‘Sacrificial Dance’ section is less a case of letting go more a punk statement of intent.

10 Joshua Redman Trios Live Nonesuch

Joshua Redman has always been a mellow listen. He makes playing the saxophone sound as natural and real as breathing, and that’s a gift. In a sense nothing has changed from the time he emerged in the 1990s only the levels of intuition are that bit more heightened and enhanced, the saxophone mastery a given. Piano-less, Trios Live could have been recorded at any time since Redman arrived fully formed as a player with something to say and the means of saying it, and his approach is still caught up in creating personality jazz in the sense that the saxophone has a personality, an individuality of sound pouring from his mouth. Released just over a year on from the Beatles, Bach, and balmy string flavours of Walking Shadows, an album that gets better and better the more you listen to it, Trios Live was recorded at New York club Jazz Standard and Washington DC spot Blues Alley, and opens bravely with ‘Moritat’, the oblique way of referring to ‘Mack the Knife’, not at all a cutting edge choice here, but taken for a walk nonetheless that manages to confound expectations. Redman is joined by drummer Gregory Hutchinson with bassist Matt Penman for the New York date; Hutchinson again but this time Charles Lloyd bassist Reuben Rogers joining Redman for the DC segment. The album comes alive after the beauty of the rendition of ‘Never Let Me Go’, on Redman’s own tune ‘Soul Dance’ three tracks in, all the off mic shouts and spilling-out energy from the band spurring the saxophonist on and there’s plenty of sinewy, and very involved, blowing from the leader on ‘Act Natural’ the next track, almost the sub-title of a work that values authenticity and not just because it’s a live album. The a cappella soprano sax opening flourish on ‘Mantra #5’ is, if you like, the sorbet, the tangy Thelonious Monk tune ‘Trinkle Tinkle’ next not as much of a surprise as the inclusion of Led Zep tune ‘The Ocean’ somehow Redmanised the jazz club crowd getting behind the sax player as he slap tongues and keys his way through to a riff-fuelled wrap where, as ever, he succeeds in trying a little tenderness.

9 Matthew Halsall and the Gondwana Orchestra When the World Was One Gondwana Records

The north-west of England and the Manchester scene might well have a strong case in claiming that it’s the home of spiritual jazz these days, that strand of the music that places John Coltrane, Alice Coltrane and the groundbreaking free jazz and Eastern-influenced music of the 1960s centre stage. Scaling up, the 8-piece Gondwana Orchestra inject fresh moods and colours to trumpeter Matthew Halsall’s already impressive body of work. The most striking element of When the World Was One is the melding of Rachael Gladwin’s harp with the textures of the koto of Keiko Kitamura within the ensemble where Nat Birchall, whose recent album Live in Larissa was something of a career high, does much of the heavy emotional lifting work powered by the drums of Luke Flowers, Halsall taking a quite emotive solo on ‘Falling Water’. Seven tracks in all, recorded in Manchester in April 2012, the album opens with the title track, which immediately captures a mood effortlessly retained throughout. Birchall on soprano saxophone at first pairs with flautist Lisa Mallett as the tune unfolds after his opening statement as Taz Modi “goes fourth” with the tune’s softly unfolding modal vamps the motor quietly running beneath everything. ‘Tribute to Alice Coltrane’ at the end nods to ‘Journey in Satchidananda’ Gavin Barras’ attractively resonating double bass setting up quite a finale. An album, where modality and mindfulness are key, to enjoy.

8 Bałdych & Herman The New Tradition ACT

7 Black Top # One with Special Guest Steve Williamson Babel

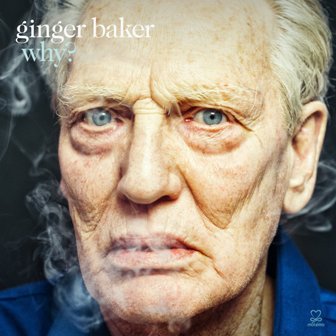

A quartet record recorded at Real World in February this year the Cream legend joined by JBs great, tenor saxophonist Pee Wee Ellis, Generation Band bassist Alec Dankworth tremendous here, and the percussionist Abass Dodoo yin to Baker’s yang, at once a curiosity, as Baker isn’t often heard these days on record playing jazz although he’s been touring a lot recently with his Jazz Confusion band, the unit here. But it also connects with Baker’s jazz past: relatively recent as ‘Ginger Spice’ was written by trumpeter Ron Miles who Baker worked so well with on Atlantic record Coward of the County at the end of the 1990s; and long gone past, a paean to Baker's Graham Bond Organisation days. Baker, as you can see above on the album cover looks right at the camera defiantly, the drum icon’s face shrouded by smoke. That swirling constantly changing sense is also here on the eight tracks, Pee Wee Ellis’ ‘Twelve and More Blues’ allowing Baker to eventually seem like he could even be the musical granddad of Seb Rochford. The loping delicious sound of ‘Cyril Davis’ or ‘Cyril Davies’ as it should be (again a link to Coward of the County) Baker’s tune next, a nod to 1960s harmonica ace Cyril Davies who Baker used to play with in Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated brings out a lot of soul from Pee Wee here exhibiting some of his strongest playing in years, Dankworth coming alive. The spirit of the revolutionary jazz and blues of the 1960s rarely equalled in jazz history has never left Baker and it’s on display here, and it’s fitting that one of the great ballad anthems of that decade is included with a puckish take on Wayne Shorter’s ‘Footprints’ from 1966, Baker sensibly taking the tempo up a notch as Pee Wee delves deep into the nuts and bolts of the tune. Baker’s ‘Ain Temouchant’ sees Ellis come over like Sonny Rollins and it’s a handsome sound full of character. Newk’s ‘St Thomas’ is the next track appropriately enough, though it’s the least effective treatment here, more a jog along than anything else. The Nigerian traditional piece arranged by Baker, ‘Aiko Biaye’, is a good reminder that Baker and Fela Kuti had an understanding and Why can easily be said to be an AfroJazz album. The title track at the end has a humongous groove beginning briefly like the beat behind ‘Coming Home Baby’ before a spell of offbeat hi-hat clashing, Dankworth coming back to reprise that ‘Coming Home’ thumping momentum and a melody that has a ‘Wade in the Water’ spiritual feel to it Baker scrapping away with a little vocal response from Kudzai and Lisa Baker. No need to ask why at all, just let Baker be.

5 Steve Lehman octet Mise en Abîme Pi Recordings

Brilliant altoist Steve Lehman embedded deep inside this post-MBASE “spectral” soundscape influenced by Tristan Murail and Gérard Grisey powers into overdrive here with trumpeter Jonathan Finlayson, tenorist Mark Shim (who appears on Marko Churnchetz’s upcoming quartet album Devotion), trombonist Tim Albright, vibist Chris Dingman using alternate tuning, tuba player Jose Davila, bassist Drew Gress who appeared on Ralph Alessi’s magisterial Baida last year, and drummer Tyshawn Sorey. Five years on from Travail, Transformation and Flow, Lehman expands on his interests in timbre, electronics, and microtones, and the album is also a brainy homage to Bud Powell with three reconstructions of the bebop pioneer’s compositions contributing to Lehman’s own ‘Glass Enclosure Transcription’, ‘Autumn Interlude’, and ‘Parisian Throughfare Transcription.’ A free flowing fry-for-all.

4 Billy Hart Quartet One Is the Other ECM

It’s free-jazz in the sense of an absence of ‘beat’, say on Billy Hart’s own tune ‘Amethyst’, the presence of fundamental pulse, and above all the interdependence of individual improvisers who track each other's every move every inch of the way, that counts here. And it’s the manner in which the oblique acoustic quartet excursions embrace strong melodic passages that then emerge to bloom rather than shrivel to expire that's remarkable. The ‘tradition in transition’ (that's the path trod by Ornette and Paul Bley, Bill Evans and Paul Motian, and, diverging, Tristano and Warne Marsh) surfacing on the only standard here, the yearning ‘Some Enchanted Evening’ where Hart’s time keeping drawing a little on the well of bassist Ben Street’s tonal resourcefulness achieves maximum impact. Pianist Ethan Iverson accompanies saxophonist Mark Turner quite beautifully on ‘Sonnet for Stevie’ where Hart’s time keeping and deftly sublimated swing amount to something to savour.

3 James Brandon Lewis, Divine Travels, OKeh

This record enters the pores. The ghosts of the past a phantasmagorical challenge to the present: the spirit rising to conquer in the person of saxophonist James Brandon Lewis, a player whose sound is soaked in the deeply spiritual healing waters of free jazz. There’s that sense that what you’re hearing is special, the raw material cut by Herculean effort from some sort of fabled marble hidden in a far away quarry. Divine Travels finds Lewis with bassist William Parker and drummer Gerald Cleaver, two avant garde prophets from that influential sound world where John Coltrane was ultimately the father, Pharoah Sanders the son, and Albert Ayler the holy ghost. Lewis’ second album four years on from Moments among its 10 tracks there’s impressive input from the Washington DC-born poet Thomas Sayers Ellis. And above all there’s a remarkable calm here for instance on the track ‘Divine’ but contrast this with the quick witted breathlessness of ‘A Gathering of Souls’ or the way ‘Tradition’ opens out for a sunny walk in the park for Parker and Cleaver, Lewis chipping in as the rhythm envelops all three. There’s a lonesome ache to ‘Enclosed’ Parker tearing at the limits of the bass as Lewis becomes almost conversational in a Sonny Rollins sense Cleaver opening everything up with deft touches and the universality of rhythm. ‘No Wooden Nickels’ has so much poise, Lewis drawing deep from some secret well of inspiration, Sayers Ellis a syllabic syncopating foil to Lewis on ‘Organized Minorities’. A brilliant inspirational record everyone should hear.

2 JD Allen Bloom Savant

The tenor saxophone hero here with cultured pianist Orrin Evans, practically Bley-like, LaFaro-calibre bassist Alexander Claffy, and drummer Jonathan Barber, summoning Rudy Royston-like rolls and routines on ‘The Secret Lives of Guest Workers’, recorded in a New Jersey studio in January this year an album that draws, Allen says in the notes, on 20th century classical music (Messiaen and Schoenberg); the Great American songbook; and jazz improvisation. Allen is one of the tenor saxophonists closest to the spirit of John Coltrane playing today, the Detroit-born 41-year-old sends you into a space of retreat to emerge somehow exhilarated. Music for the mind and the body Allen’s last record as a leader was Grace and you may have also picked up on him on Jaimeo Brown’s groundbreaking 2013 record Transcendence. An awesome record, words are pretty much unnecessary, but pick your jaw up off the floor as you’ll need it to chew over Bloom with your friends. Mostly JD’s tunes plus Tadd Dameron’s cool ballad ‘If You Could See Me Now’, a song Sarah Vaughan made her own in the 1940s, all stillness and dewy, and Hoagy Carmichael’s ‘Stardust’ glistening and iridescent. The traditional ‘Pater Noster’ will give you chills. A marvel.

1 Ambrose Akinmusire The Imagined Savior Is Far Easier To Paint Blue Note

On extraordinary form once more trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire with his longstanding quintet here extended on a perplexingly-titled album by a string quartet, plus The Vigil guitarist Charles Altura, and singers Becca Stevens, Theo Bleckmann (who features on the new Michael Wollny record Weltentraum) and the startling Canadian singer/songwriter Cold Specks. Apocalyptic in mood, with a strong socially conscious side to it, the album opens with ‘Marie Christie’, pianist Sam Harris’ babbling brook-like accompaniment behind Akinmusire’s moody flurry of an exposition. Harris sets up ‘As We Fight (Willie Penrose)’ in a different, more narratively-inclined way, placed against snare drum patterns, and Altura’s guitar fits in snugly behind the horns, Justin Brown’s martial beat urgent and vital. ‘Our Basement’ next brings in the voice and lyrics of Becca Stevens and it’s a dramatic moment at this stage of the album, the voice very moody and engagingly strained, the OSSO String Quartet, who have already worked with Jay-Z, Ravi Coltrane, and The National among others, adding a new dimension that expand the range and ambition of the music. ‘Vartha’ has a guitar opening from Altura with a lovely Harish Raghavan bass figure the response and fleeting tambourine rhythm and then a very different aspect to Akinmusire’s tone, a little Thad Jones-like, as the melody of the ballad snakes around a ‘Footprints’-like sequence of notes momentarily to open out. ‘Memo (G. Learson)’ begun by a sinewy Brown drum solo leaning into a finely honed arrangement that blends Walter Smith III’s tenor with Akinmusire’s trumpet a little like the way Terence Blanchard and Brice Winston work together and Smith’s solo draws out the band, its open spirit enabling Harris to find a new space and then Akinmusire flies, the fluttery rapid fire almost Dizzy-like flavour to his style here quite striking. The violins opening ‘The Beauty of Dissolving Portraits’ catch you off balance transporting you back in time to an historic long-gone America momentarily, then the flute and a plangent wash of textures develop as Akinmusire joins. Akinmusire’s writing is very original throughout and I think it’s a more confident album than 2011’s highly acclaimed album When The Heart Emerges Glistening and more experimental then both that record and the earlier Prelude: to Cora. Bleckmann’s velvety opening to ‘Asiam (Joan)’ is the male vocal match to the earlier Stevens track, a fine balancing touch, and this song is more impressionistic as it turns out regardless of the classic balladic opening verse with the singer and the ensemble closely united experimentally as the song unfolds. The highly rhythmic ‘Bubbles (John William Sublett)’ dedicated to the tap dancer and entertainer who played Sportin’ Life in Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, gives bassist Raghavan plenty of room to manoeuvre in a composition that builds on repetitive devices, while ‘Ceaseless Inexhaustible Child (Cyntoia Brown)’ has an achingly tender beginning and an unforgettable vocal on this modern day spiritual from Cold Specks singing her own words on a song whose dedicatee is a tragic 16-year-old who killed. ‘Rollcall For Those Absent’ with the voice of a little child reciting a list of names familiar from news reports including Timothy Stansbury, Amadou Diallo, and Trayvon Martin’s, victims of racism in America, builds on the social commentary while the liturgical aspect of Akinmusire’s work beyond the oblique reference in the album’s title surfaces explicitly and in a spirit of humility on the increasingly free-form ‘J E Nilmah (Ecclesiastes 6:10)’, the biblical text referred to in the tune's title, ‘Whatever exists has already been named, and what humanity is has been known; no one can contend with someone who is stronger.’ ‘Inflatedbyspinning’ has an almost 18th century-like chamber dimension to it led off by the strings, while ‘Richard (Conduit)’ has a rolling free anarchic energy where Walter Smith III excels to complete an absorbing and rewarding album that strengthens further Akinmusire’s reputation as an improviser and composer of considerable clout.