//

The trad era, with the passing of luminaries Kenny Ball, Terry Lightfoot at the weekend, and the writer Jim Godbolt earlier this year probably turned away as many people from jazz as it attracted to it, a paradox unseen in its day as trad reached the largest audiences jazz has ever reached in this country.

With their subsequent outlandishly outmoded stage wear, and the music seemingly reluctant to move beyond banjo-and-braces clichés it’s no wonder that trad became seen as part of a cultural backwater eventually, a garden gnome of a genre.

With the birth of rock ’n’ roll it became a joke, and the music identified with your parents’ generation. Former rock journalist John Harris, writing in The Guardian has put it like this: “I came of age in a culture in which the jazz both categorised and demonised as ‘trad’ would not do at all. I have childhood memories that fit the picture – of impatiently flicking through the three TV channels, and alighting on ensembles of men in candy-striped waistcoats, blowing out a racket that seemed dated, even flatly silly.”

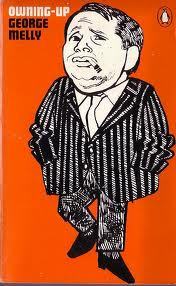

Poet Philip Larkin used trad partly as a criticism of modernism in his jazz critiques, while Melly tells how, rather than taking sides, he found that in the Scala theatre in London’s Charlotte Street he discovered the power of ‘revivalist jazz’, the term used before ‘trad’ supplanted it. “I came out of that concert a changed person,” Melly wrote in Owning Up first published in 1965, when trad was a distant memory. Now the music is still widely played in under-the-radar places, often very stubbornly, to an often baffled, uninterested, and dwindling audience.

Melly discovered the revivalist scene via the Melody Maker and began to sing with Beryl Bryden at the Leicester Square Jazz Club and later Eel Pie Island eventually joining Mick Mulligan’s band, a big hero of Melly’s whose picaresque adventures the singer was so adept at telling so very entertainingly.

Trad for Melly was a state of mind, and it was about fun, not a word that the young maths-jazzers today like to use overly much. The venues then were pretty unrecognisable from today’s jazz places, according to Melly’s description. “Many of those pub rooms were temples of the ‘Ancient Order of Buffaloes’, that mysterious proletarian version of the ‘Freemasons’, and it was under dusty horns and framed nineteenth century characters that we struggled through ‘Sunset Café Stomp’ or ‘Miss Henry’s Ball’."

Melly is astute enough to mention that some traditionalists became modernists or mainstreamers, and some trad musicians “began to realize that Gillespie and Parker, Monk and Davis were not perverse iconoclasts but in the great tradition.”

Yet there developed a schism between the two big styles in jazz of the day, a lack of toleration, that carried a heavy toll. With Larkin ludicrously pitting Miles Davis (bad) on the one hand against Eddie Condon (good) on the other the madness of the rivalry, and the prejudices involved still scream off the page. “As it enters the ear,” Larkin wrote, “does it come in like broken glass or does it come in like honey?”

There are a few figures from the trad era still left and topping festival bills, most notably Acker Bilk who appears at Brecon in the summer, and the constantly touring Chris Barber. Although the years of trad as a popular movement disappeared long ago just as the craze for jungle or grime in recent years has, trad has endured long beyond its natural shelf-life, and will in all likelihood live on past the departure eventually of all of the trad gentlemen of jazz. Will a new generation, even if it wanted to, manage to capture that initial excitement that made trad significant in the first place? Maybe not. Remixing ‘Petite Fleur’ or performing a punk jazz revamp of ‘Stranger on the Shore’, might have to wait a while yet.

The cover of Owning Up, pictured top