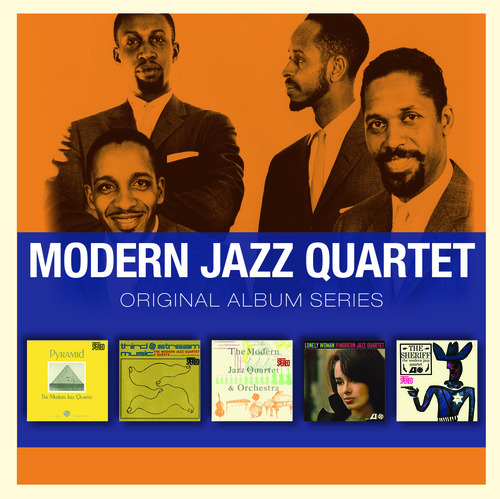

This coming Monday sees the release of this beauty Modern Jazz Quartet: Original Album Series in a line that values two things: one, respect for the integrity of the original albums; and two simplicity in design. There are more on the way, including one featuring the music of Billy Cobham to look forward to, timely with the current focus on the music of Massive Attack the trip hop pioneers who sampled ‘Stratus’. http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2012/dec/06/massive-attack-blue-lines-review

The MJQ couldn’t be further away from Cobham, the jazz-rock of the 1970s and Massive Attack. They stood for something that a recently reprinted Benny Green review was scornful of in 1959:

The Modern Jazz Quartet is one of the most astonishing cultural phenomena of the postwar period. For the last five years, four men have sought with painful eagerness to transform the racy art of jazz into something aspiring towards cultural respectability. The photographs on the covers of their bestselling albums show three bearded men and one bespectacled man in morning coats, looking at the camera with the studied gloom of four eminent Victorians who have just heard about On the Origin of Species.

The attempt of their pianist, John Lewis, to make jazz socially acceptable is an excellent idea. Better morning coats and gloom than tales of Al Capone and bootleg days. The snag is that this courting of respectability has drained away so much of the vitality of their music that there is little left but a few flickers of animation from the brilliant vibraharpist Milt Jackson and occasional passages reminiscent of Bach, of all people.

The group’s instrumentation is piano, drums, bass and vibraharp. The sound is necessarily so introspective that 10 minutes after the opening of their concert in the Festival Hall last Saturday one became acutely conscious that the quartet had only two degrees of dynamics, soft and very soft. The earthiness of jazz has been replaced by a fey tinkling.

Lewis’s integrity as a jazz musician is unquestioned. He has vast experience as a musician with most of the outstanding soloists of the last 10 years. He has decided, however, that jazz must become international in the sense that it must be made to portray people and places generally considered incompatible with jazz. Most of his theme titles are French. The one essential element in any jazz performance, the preservation of the illusion of improvisation, he has cast to the winds, pursuing instead rarer and rarer refinement.

There was one moment when the irony of the situation would have been enough to make a cat laugh. The group played a tune written by Duke Ellington called It Don’t Mean a Thing if it Ain’t Got That Swing. The tune is one that respects the edict of its own title, being constructed in such a way that provided it is taken at the intended tempo, it cannot possibly be played in a dull manner. Or so I would have thought. The quartet did a better job of demolition on Ellington’s theme than any other group, band or orchestra I have come across.

The reaction of British audiences has been hysterical, audiences comprising the same people who abandoned Ellington to half-empty houses last year. My own feelings coincide with those of a fellow musician I met later on Waterloo Bridge. “It suddenly occurred to me," he said, “that there were three thousand of us sitting there watching a man with a small beard hit a small bell with a small stick."

The Observer

But the MJQ were misunderstood, and still are, so this reissue is important. These albums: Pyramid, Third Stream Music, MJQ and Orchestra, Lonely Woman, and The Sheriff, show in one place (listen to them at one sitting, draw the curtains, switch off your phone, they’re better than the TV), that they were (if you like) experimenting with tradition, with European classical music, and their own interpretations of small group jazz.

In a way it’s the advanced exemplification years on, without a distracting and limiting jam session ethos, of Jazz at the Philharmonic, which Norman Granz developed for the swing giants in the 1940s.

All four of the band as we know it (Kenny Clarke was the original drummer but left to forge a career in France), that’s of course John Lewis, Milt Jackson, Percy Heath and Connie Kay, began in Dizzy Gillespie’s late-1940s band, with the MJQ beginning in 1951.

The quartet, with many breaks and stops and starts, recorded under that name for some 40 years following. The pick of the albums collected here is Pyramid for me. ‘Django’ is as significant a piece as ‘Take Five’ or ‘Round Midnight’. It’s as cool as they come, with the poise of the night air, the contemplative quality of a thought you wish you’d had and want to cling on to, and the knowledge as a listener that the tune has a depth it’s your duty to discover. The MJQ put the onus on you, as it’s challenging music, doubly so because it uses forms and structures that are familiar but refashioned in their own image. It’s like recognising the face of a friend but having to look closely into their eyes to really know what they’re thinking. That’s hard. Sure there’s recessed bebop here, and this thing called “third stream" that nearly everybody misunderstands but really should only be applied to MJQ and Gunther Schuller’s ideas of the day as he came up with the term.

The MJQ didn’t create a hybrid music that shackles jazz to classical music. That’s the big lie. They used classical music as a writer might use a dictionary, and their music like the best repository of words is a well of knowledge and an inspiration still, unlike the cheap insult of someone a critic happened to meet on Waterloo Bridge and took as their mantra.

Stephen Graham