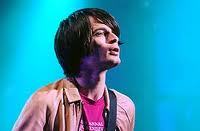

A few thoughts immediately spring to mind about The Master. First of all it’s a very long wait until November when the film, the latest by Paul Thomas Anderson is released. Anderson, for Magnolia and more recently There Will Be Blood, is one of the artiest of ‘commercial’ arthouse directors possessing the unique ability to combine the most arresting of visual images (think the frogs raining from the sky to the waifish wailing of Aimee Mann or the gushing of Brahms to the blackest of an oil well in spate in Blood) to music. Secondly, with a score once again on an Anderson film by Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood (pictured below), there is beyond the gloriously fractured themes infused by the spirit of the Polish classical avant garde (Penderecki, who Greenwood has worked with, and maybe Lutoslawski) music which accompanies a plot that concerns itself with the story of a Naval veteran played by Joaquin Phoenix coming home from war who falls under the spell of The Cause (pick a cult, any cult) led by its maverick and slightly disturbing leader, played by Philip Seymour Hoffman, who you’ll remember was the much put upon nurse in Magnolia.

From what I’ve heard so far of the score it has a substantial, fibrous feel to it, with plenty of crunch points that effortlessly point to a sense of mystique without appearing to do so in an obvious way. The Master is debuting at The Venice Film Festival this week and undoubtedly early reviews will appear in the national press shortly.

The other aspect that occurs to me that is worth mentioning is the way the extra music in the film, whether it is ‘Get Thee Behind Me Satan’ sung by Ella Fitzgerald, or ‘Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree (With Anyone Else But Me)’ performed by Madisen Beaty, or the spooky version of Chopin’s Tristesse ‘No Other Love’ by Jo Stafford or best of all the ambiguous ‘Changing Partners’ by Helen Forrest (pictured top) makes you revisit songs that on a reissued CD would not be so gripping all together. That’s partly the skill of the juxtaposing of this often old-sounding music with the very modern Greenwood score, so the context changes the perception. Older readers will recall Forrest who had wartime hits with the Harry James band, but on this soundtrack is accompanied by the Sy Oliver orchestra.

One final thing about the music, it features Shabaka Hutchings, Neil Charles and Tom Skinner collectively Zed-U, along with veteran Humphrey Lyttelton clarinettist Jimmy Hastings and the London Contemporary Orchestra violinist Daniel Pioro on the eighth track, which is titled ‘Able-Bodied Seamen’. A certain clarinet-led experimental modernism Greenwood explores heavily on this track and adds that bit more interest for jazz people with their involvement here. So remember, remember the fifth of November when the soundtrack is released by Nonesuch: it might even send you off to explore the vocal jazz of the 1940s with renewed interest.

Stephen Graham